Orkney - an archaeologist's paradise

Make your way all the way to the very top of Scotland, and you’ll find John O’Groats. Keep going and you’ll reach Orkney, a collection of 70 small islands and home to some of the most gorgeous scenery in the British Isles.

The islands also have a rich Scandinavian heritage: settled by the Vikings in the ninth century, Orkney is, says Dr Jane Harrison, Lecturer in Archaeology at the Department, ‘an archaeologist’s paradise’. Dr Harrison began working on a dig in the islands in 2004, with Dr David Griffiths, the Department's Director of Studies in Archaeology, who directed the Birsay-Skaill Landscape Archaeology Project, and Dr Michael Athanson, an archaeologist and map specialist at the Bodleian. The three have just published a major book about the work, Beside the Ocean: Coastal Landscapes at the Bay of Skaill, Marwick, and Birsay Bay, Orkney: Archaeological Research 2003-18 (Oxbow Books, 2019).

The dig location, at the Bay of Skaill on Orkney’s west coast, is ‘stunning’ says Dr Harrison, though often windy: ‘It can be a bit rough but very beautiful.’ From an archaeologist’s point of view, what makes Orkney so interesting is that ‘a lot of the sites are in rural areas that haven’t been touched by development’. Orkney was one of the first areas to be settled by the Vikings when they moved out of Scandinavia, but until the team started work, only a small number of their settlement sites had been scientifically investigated. This meant there was a very rich history waiting to be discovered.

It’s not surprising, then, that each summer the dig attracted plenty of volunteers – a mix of students from the Department, undergraduates from other universities, local Orcadians and even commercial archaeologists choosing to work on the dig as part of their summer holiday. Team members came, not just from the UK, but from as far afield as Norway, Ireland, the USA, Holland and the Czech Republic.

‘It was a lovely place to work,’ says Dr Harrison. ‘After the first couple of seasons when we became part of the landscape, people were so helpful and friendly. We’d turn up and they'd say, “Oh, you’re back.”’

Digging through sand

The team investigated three areas on Orkney’s West Mainland. Before digging could start, a programme of geophysics (which detects magnetic differences in the soil) was able to establish the existence of walls and ditches, indicating the most promising places to dig. It was a little tricky, says Harrison, because in a lot of areas in Orkney the main geology above bedrock is ‘windblown sand’ and magnetometry becomes a bit ‘bamboozled’ by sand. They also had to plan how to dig safely in sand, and where to put the sand after they’d dug it out. Along with Orkney’s windy weather, it was a challenge – but ‘a nice meaty challenge’, says Dr Harrison.

Another difficulty was that the Vikings’ approach was to build on ‘very prominent hillocks and rises on bays so they could see and be seen, and then to rebuild in the same place, which means you get this layer cake of walls and floors. If you look at them from the air, they’re very jumbled and difficult to interpret.’

A thrilling discovery

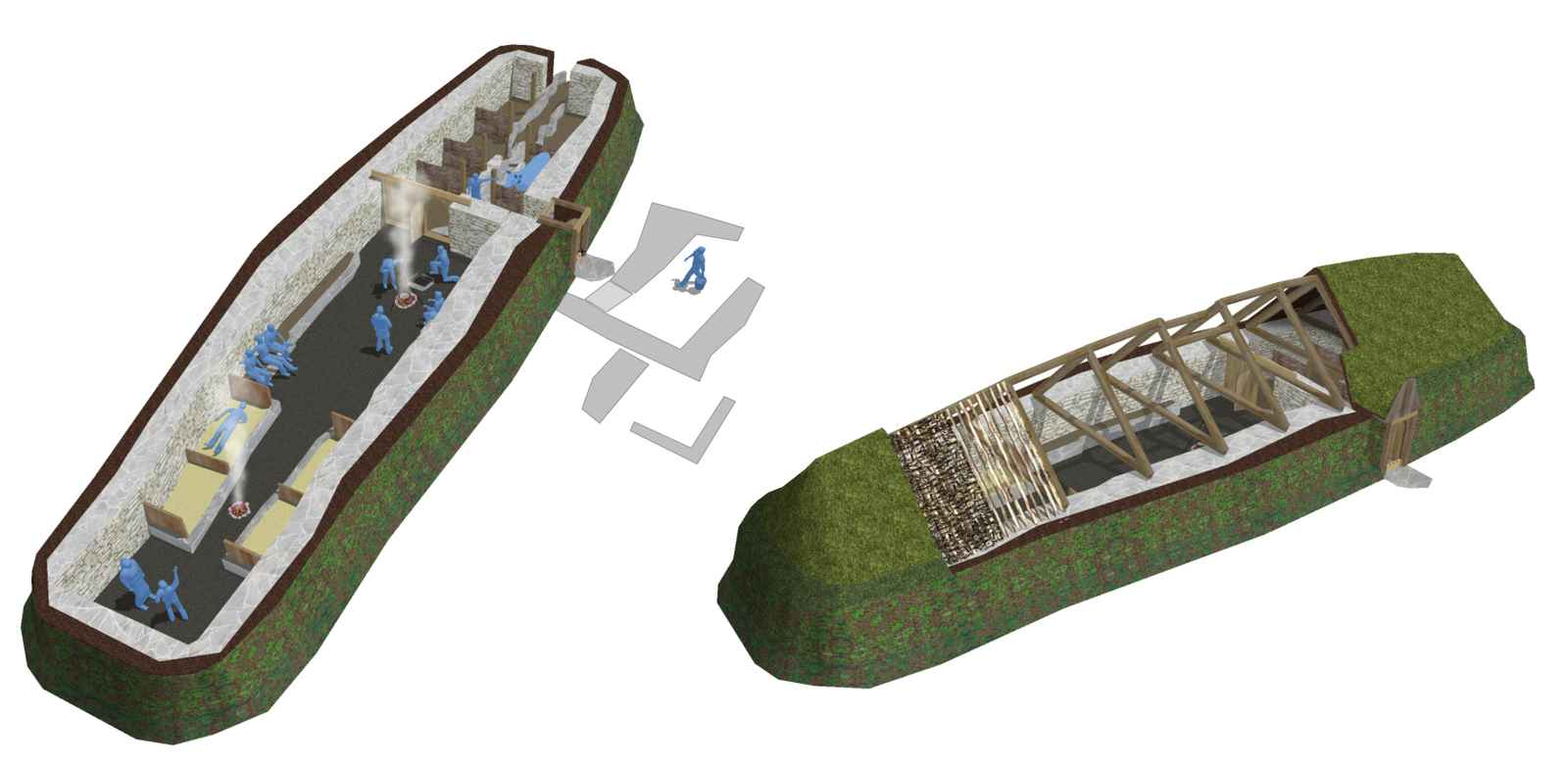

Some of the geophysical work helped provide context for earlier archaeological discoveries. But there were also brand-new discoveries. The most ‘thrilling’ part of the excavation was finding ‘an absolutely beautifully preserved set of longhouses,’ says Dr Harrison. Both longhouses had extra external buildings and workshops. ‘Because everything is built in stone there, and there’s no wood, things are better preserved, down to small details of little shelves and seating.’ The walls themselves were over a metre high. Seats were created by sinking slim upright stones into the sand, says Dr Harrison, and then adding furs or textiles on top. ‘All those bench fronts survived, as well as the stone surrounds for fireplaces and little inbuilt shelves.’ These buildings were most evocative; ‘We were able to sit the excavation team along the very stone benches Viking groups occupied, facing the fireplace in the shadow of the same walls that sheltered people then.’

In much of the UK, the Vikings blended in with the local culture, but in Orkney, says Dr Harrison, they maintained their own Scandinavian culture. As far back as 1858, a child had found a silver hoard in the proximity of what turned out to be the two longhouses. The dig was able to provide some context to the old find. It was a ‘really beautiful and incredibly valuable and high-status hoard,’ says Dr Harrison, but in comparison the buildings ‘weren’t staggeringly high status, so people were demonstrating their power in ways other than huge buildings.’

Among the artefacts found by the team were pieces of carved bone combs. ‘The Vikings made beautiful combs – they were a signal of your belonging and your identity,’ says Dr Harrison. A particularly striking one was a comb found next to an iron candlestick, some dog bones and pottery, in a ‘deliberate caching of objects underneath a floor’ when the longhouse was abandoned.

After so many years working on such an interesting project, would Dr Harrison like to return to Orkney? ‘I’m beginning to get a handle on how it works archaeologically, so you do feel it would be nice to go back and take your experience to another site,’ she says. ‘There are some that would be really good to explore – but we’ll see.’

Find out more on our website about Dr Jane Harrison and Dr David Griffiths and our courses in Archaeology.

To learn more about the book visit the publishers website.

Main image: the longhouse under excavation

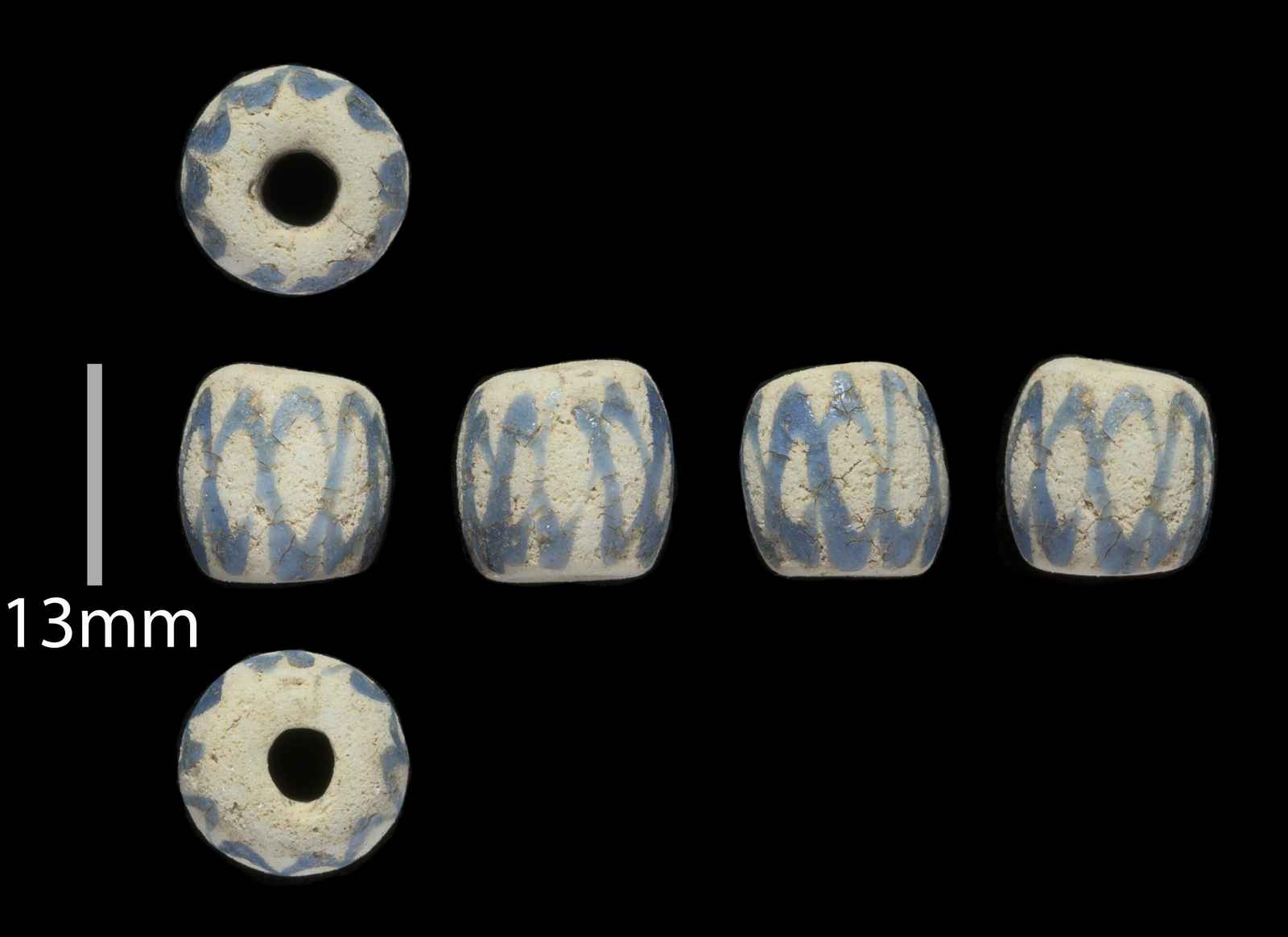

Gallery images: Reconstruction of the longhouse and some of the finds (comb and a glass bead).

Published 11 July 2019