Where the bodies are buried

Oxford is known internationally as the home of Inspector Morse – and as such, Oxford is seen by many as a place where a body or two might crop up at any time.

At Rewley House in central Oxford, we can tell of fully twenty bodies discovered here one sunny summer day.

A minor building project unearths a surprise

On 30 June 1994, contractors were working behind Rewley House to make a flight of steps from the Acland Room into the garden behind the building. This small rectangle of land had been acquired only recently from the property at 40 St Giles, to the east of Rewley House.

The work to build the stairs required an L-shaped area of earth to be excavated – an area measuring some two and a half meters.

Workmen had only just started to dig when they began to uncover bones. Work was immediately suspended – and Continuing Education archaeologists Gary Lock and Trevor Rowley were informed.

Janet Hufton, who has worked in the finance office of the Department since the late 1980s, remembers the day.

‘Archaeologist Sheila Raven and I walked out onto the roof of the Rewley House dining room and peered over the wall down into the hole the workmen had dug,' Janet recalled. 'There were several skulls visible. Sheila climbed down there on a ladder to investigate.’

The workmen’s machinery had exposed seven skulls and an assortment of bones, which were discovered stacked against the wall of Rewley House, about 1.8 metres below the present level of the garden. A tentative probe produced three more skulls, before work was suspended.

On 5 July an official excavation was begun by Department archaeology staff members Sheila Raven and Melanie Steiner, Archaeology Diploma student Emma Hodgetts, and Oxford Archaeology Unit’s Angela Boyle. The work was directed by Gary Lock and Trevor Rowley. Local historian Kate Tiller researched the history of the land.

The history prior to Wellington Square

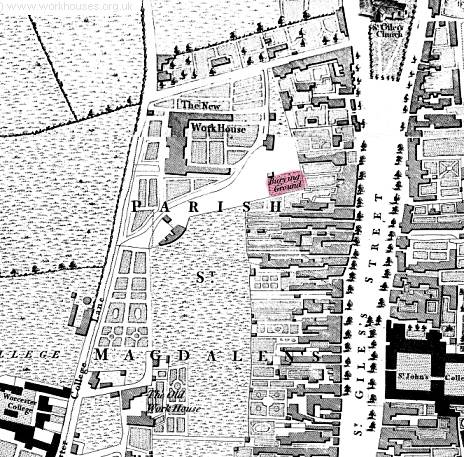

What we now know as our lovely Acland Garden had once been part of a cemetery used by Oxford’s Workhouse. The workhouse stood where Wellington Square is today, and its cemetery was located in the south-east corner of the site (shaded in pink on the attached map).

What we now know as our lovely Acland Garden had once been part of a cemetery used by Oxford’s Workhouse. The workhouse stood where Wellington Square is today, and its cemetery was located in the south-east corner of the site (shaded in pink on the attached map).

It is known that the eleven central parishes of Oxford were united for poor law purposes under a Board of Guardians in 1771. The workhouse was constructed in 1772, on a five-acre area then-called “Rats and Mice Hill”. Prior to the workhouse a Civil War defence, built 1642-46, ran across this area.

The workhouse was designed by John Gwynn (who was also the architect of Magdalene Bridge) and constructed at a cost of £4,030. It was built to house 200, but later was extended.

In the 1860s, a new workhouse was built in east Oxford – and the old workhouse site became Wellington Square.

Constructed between 1869 and 1876, Wellington Square was conceived as a speculative development of mixed domestic housing.

Terraced houses, a school and the garden square were built on the footprint of the old workhouse – but a portion of the paupers' cemetery remained untouched and unused. Over time, with no headstones to mark the graves, the land’s original purpose faded from memory into obscurity – until 1994.

Excavation and reinterment

The excavation of the old workhouse cemetery found traces of reused medieval dressed stone in the wall of the old cemetery; however, it was assumed that the wall itself dated from when this piece of land began being used as a burial ground, in workhouse days. Prior to the arrival of the workhouse, most of the land in this part of Oxford was ornamental strip gardens attached to the houses on St Giles, to the east.

Interestingly, the wall running east-west at the south side of the Acland Garden is of some considerable age, being part of the old North Gate Boundary Hundred wall. (‘Hundreds’ as administrative units date back to the Anglo-Saxon era and were still in use in the 19th century, for example, to define Poor Law Workhouse areas.)

The archaeological excavation revealed evidence of some twenty bodies, a few of which remained articulated. The skeletons were the remains of men, women and several babies. They had evidently been buried in coffins in some seven layers, and laid to rest over a period of time. The soil was full of nails from wooden coffins which had rotted away, the collapse of which had caused the skeletons to be stacked up and somewhat compressed atop each other. Also found on site were shroud pins, clay pipe remains and pottery.

The excavation was completed on 14 July, after seven days of work. The bones were then washed, documented and boxed.

Commenting on this episode in the Department's history, former Department Director Geoffrey Thomas said: 'After the initial shock of the discovery, we were determined that the poor souls who were resting here should be treated with respect and given a proper burial.'

So it was that several weeks later, Department staff gathered in the churchyard of nearby St Giles Church, where a new grave had been dug. The (re)burial service was presided over by Canon Vincent Strudwick, Director of the Theology and Religion Programme, and the bones were laid to rest once again.

A wake was held at Rewley House that evening, to honour the dead, and to reflect on Continuing Education's relatively short tenure in this historical place. Inspector Morse would have approved.

Published 13 April 2017